R H Mathews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

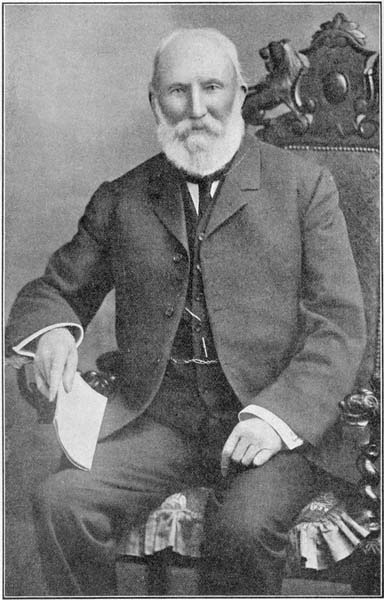

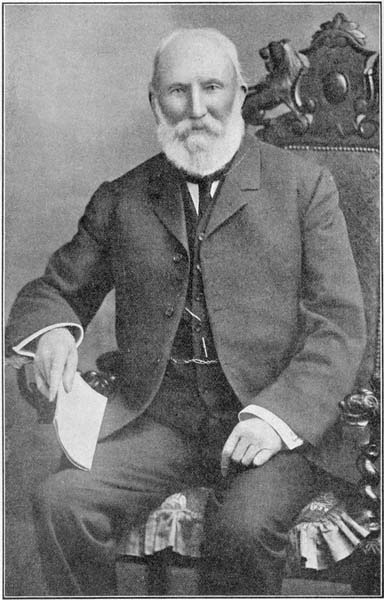

Robert Hamilton Mathews (1841–1918) was an Australian surveyor and self-taught

Robert Hamilton Mathews (1841–1918) was an Australian surveyor and self-taught

Robert Hamilton Mathews papers

has allowed greater understanding of his working methods and opened access to significant data that were never published. Mathews' work is now used as a resource by anthropologists,

Robert Hamilton Mathews papers

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mathews, Robert Hamilton 1841 births 1918 deaths Australian anthropologists Linguists from Australia

Robert Hamilton Mathews (1841–1918) was an Australian surveyor and self-taught

Robert Hamilton Mathews (1841–1918) was an Australian surveyor and self-taught anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

who studied the Aboriginal cultures of Australia, especially those of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and southern Queensland. He was a member of the Royal Society of New South Wales

The Royal Society of New South Wales is a learned society based in Sydney, Australia. The Governor of New South Wales is the vice-regal patron of the Society.

The Society was established as the Philosophical Society of Australasia on 27 June ...

and a corresponding member of the Anthropological Institute of London (later the Royal Anthropological Institute

The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI) is a long-established anthropological organisation, and Learned Society, with a global membership. Its remit includes all the component fields of anthropology, such as biolo ...

).

Mathews had no academic qualifications and received no university backing for his research. Mathews supported himself and his family from investments made during his lucrative career as a licensed surveyor. He was in his early fifties when he began the investigations of Aboriginal society that would dominate the last 25 years of his life. During this period he published 171 works of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

running to approximately 2200 pages. Mathews enjoyed friendly relations with Aboriginal communities in many parts of south-east Australia.

Marginalia in a book owned by Mathews suggest that Aboriginal people gave him the nickname Birrarak, a term used in the Gippsland

Gippsland is a rural region that makes up the southeastern part of Victoria, Australia, mostly comprising the coastal plains to the rainward (southern) side of the Victorian Alps (the southernmost section of the Great Dividing Range). It covers ...

region of Victoria to describe persons who communicated with the spirits of the deceased, from whom they learned dances and songs.

Mathews won some support for his studies outside Australia. Edwin Sidney Hartland

Edwin Sidney Hartland (1848–1927) was an author of works on folklore.

His works include anthologies of tales, and theories on anthropology and mythology with an ethnological perspective. He believed that the assembling and study of persistent a ...

, Arnold van Gennep

Arnold van Gennep, in full Charles-Arnold Kurr van Gennep (23 April 1873 – 7 May 1957) was a Dutch–German- French ethnographer and folklorist.

Biography

He was born in Ludwigsburg, in the Kingdom of Württemberg (since 1871, part of the Ger ...

and Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectures at the University ...

were among his admirers. Lang regarded him as the most lucid and "well informed writer on the various divisions which regulate the marriages of the Australian tribes." Despite endorsement abroad, Mathews was an isolated and maligned figure in his own country. Within the small and competitive anthropological scene in Australia his work was disputed and he fell into conflict with some prominent contemporaries, particularly Walter Baldwin Spencer

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (23 June 1860 – 14 July 1929), commonly referred to as Baldwin Spencer, was a British-Australian evolutionary biologist, anthropologist and ethnologist.

He is known for his fieldwork with Aboriginal peoples in ...

and Alfred William Howitt

Alfred William Howitt , (17 April 1830 – 7 March 1908), also known by author abbreviation A.W. Howitt, was an Australian anthropologist, explorer and naturalist. He was known for leading the Victorian Relief Expedition, which set out to es ...

. This affected Mathews' reputation and his contribution as a founder of Australian anthropology has until recently been recognised only among specialists in Aboriginal studies. In 1987 Mathews' notebooks and original papers were donated to the National Library of Australia by his granddaughter-in-law Janet Mathews. The availability of thRobert Hamilton Mathews papers

has allowed greater understanding of his working methods and opened access to significant data that were never published. Mathews' work is now used as a resource by anthropologists,

archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

, historians, linguists

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, heritage consultants and by members of descendant Aboriginal communities.

Family background

Robert Hamilton Mathews was the third of five children in a family ofIrish Protestants

Protestantism is a Christianity, Christian minority on the island of Ireland. In the 2011 census of Northern Ireland, 48% (883,768) described themselves as Protestant, which was a decline of approximately 5% from the 2001 census. In the 2011 ...

. His elder siblings Jane and William were born in Ulster before the family's flight from Ireland in 1839. Robert and his younger sisters Matilda and Annie were born in New South Wales. Before they emigrated, Mathews' father, William Mathews (1798–1866), was the principal co-proprietor of Lettermuck Mill, a small papermaking business near the village of Claudy

Claudy () is a village and townland (of 1,154 acres) in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It lies in the Faughan Valley, southeast of Derry, where the River Glenrandal joins the River Faughan. It is situated in the civil parish of Cumber U ...

in County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. B ...

. The other partners were his three brothers, Robert, Hamilton and Samuel Mathews. When first established by Robert's grandfather (also named William Mathews), Lettermuck was a successful business. Changes in papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

technology, combined with the introduction of the Paper Excise

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

to Ireland in 1798, adversely affected profitability. Many Irish papermakers made efforts to evade the tax on paper and the Mathews family became "notorious for crimes against the Excise". They were regularly summoned before the Court of the Exchequer to answer charges of avoidance. Between 1820 and 1826 penalties of £3,300 were imposed on William Mathews, none of which he paid.

Hostile relations developed between the Mathewses and the Excise officers who regularly inspected their business. In 1833 an Excise officer named James Lampen disappeared, having last been seen entering the Lettermuck premises. A witness heard the discharge of a firearm according to a newspaper report. In March 1833 Robert's father, William Mathews, his three uncles and a journeyman employed in the mill were arrested for Lampen's murder. They were incarcerated until May that year when the charges were dropped, reportedly because of the disappearance of a key witness and the failure to find a body, despite a substantial search. It was believed within and outside the Excise office that the Mathewses were guilty of murder. From the time of the brothers' release, Excise officers, protected by an armed guard, monitored the mill around the clock. Prevented from trading illegally, the business collapsed and eventually all the brothers emigrated to various destinations. In later years, bodies were exhumed from bog near the mill, thought to belong to Lampen and an itinerant worker in the paper industry. This raises the possibility that R. H. Mathews' father and uncles were involved in a double homicide.

Penniless after the collapse of the business, William Mathews and his wife Jane () falsified their ages so as to qualify for assisted migration to New South Wales. In the company of R. H. Mathews' two elder siblings, they arrived in Sydney on the ''Westminster'' in early 1840. William Mathews found labouring work for the family of John Macarthur at Camden, New South Wales

Camden is a historic town and suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, located 65 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district. Camden was the administrative centre for the local government area of Camden Council until July/August ...

and shepherded at another of their properties, Richlands near Taralga

Taralga is the traditional land of the Gundungurra people. Today it is a small village in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, in Upper Lachlan Shire. It is located at the intersection of the Goulburn-Oberon Road and the Lagga ...

. They seem to have been itinerant for some years. R. H. Mathews was born at Narellan

Narellan is a suburb of Sydney, New South Wales. Narellan is located 60 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of Camden Council and is part of the Macarthur region.

Narellan is known for it ...

, southwest of Sydney, on 21 April 1841. The family's fortunes improved when they acquired a farm of at Mutbilly near the present village of Breadalbane, New South Wales

Breadalbane () is a small village located in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia in Upper Lachlan Shire. It is located on the Lachlan River headwaters and not far from Goulburn. At the , Breadalbane had a population of 107.

Ov ...

in the Southern Tablelands. Goulburn

Goulburn ( ) is a regional city in the Southern Tablelands of the Australian state of New South Wales, approximately south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Canberra. It was proclaimed as Australia's first inland city through letters pate ...

is the nearest city.

Early life

In explaining his success in working with Aboriginal people, Mathews claimed that "black children were among my earliest playmates". This could refer to the family's time at Richlands where William Mathews worked as a shepherd, as did several Aboriginal men from the area. At Mutbilly the family lived on territory that R. H. Mathews later identified as the traditional country of theGandangara

The Gundungurra people, also spelt Gundungara, Gandangarra, Gandangara and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people in south-eastern New South Wales, Australia. Their traditional lands include present day Goulburn, Wollondilly Shire ...

people (also spelled Gundungurra). Mathews' father was, according to his grandson William Washington Mathews, a "broken man" by the time they settled at Mutbilly. He had sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

disputes with Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

neighbours and was several times prosecuted for minor assaults against them. R. H. Mathews and his younger siblings were educated by his father and at times by a private tutor.

Occasional visits by large survey teams inspired Mathews' interest in his future profession. After his father's death in 1866, he became an assistant to surveyor John W. Deering in 1866–67. He later trained with surveyors Thomas Kennedy and George Jamieson and in 1870 he passed the government-run examination to become a licensed surveyor.

Career as a surveyor

As a licensed surveyor in colonial New South Wales, Mathews was entitled to do government work that fell within his assigned district while also maintaining a private practice. His earnings were considerable, and rapidly eclipsed the salary of the colony's Surveyor-General. In the 1870s Mathews was posted successively to the districts ofDeepwater, New South Wales

Deepwater is a parish and small town 40 kilometres north of Glen Innes on the Northern Tablelands, New South Wales, Australia. At the 2006 census, Deepwater had a population of 307, with 489 people in the area.

Deepwater is located on the New ...

, Goondiwindi

Goondiwindi () is a rural town and locality in the Goondiwindi Region, Queensland, Australia. It is on the border of Queensland and New South Wales. In the , Goondiwindi had a population of 6,355 people.

Geography

Goondiwindi is on the MacInt ...

and Biamble. In 1880 he was posted to Singleton, New South Wales

Singleton is a town on the banks of the Hunter River in New South Wales, Australia. Singleton is 197 km (89 mi) north-north-west of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city ...

in the Hunter Region

The Hunter Region, also commonly known as the Hunter Valley, is a region of New South Wales, Australia, extending from approximately to north of Sydney. It contains the Hunter River and its tributaries with highland areas to the north and so ...

. As a surveyor he had many opportunities to meet Aboriginal people and he employed at least one, the Kamilaroi

The Gamilaraay, also known as Gomeroi, Kamilaroi, Kamillaroi and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people whose lands extend from New South Wales to southern Queensland. They form one of the four largest Indigenous nations in Aust ...

man Jimmy Nerang, in his survey team. Mathews joined the Royal Society of New South Wales in 1875 but never published in the society's journal until he took up anthropology in 1893. Private correspondence shows that he collected some linguistic data and artefacts during his early days as a surveyor.

Mathews married Mary Sylvester Bartlett of Tamworth in 1872. They had seven children, two of whom became prominent later in life. Their first-born Hamilton Bartlett Mathews (1873–1959) served as Surveyor-General of New South Wales

The Surveyor-General of New South Wales is the primary government authority responsible for land and mining surveying in New South Wales.

The original duties for the Surveyor General was to measure and determine land grants for settlers in New Sou ...

. Gregory Macalister Mathews

Gregory Macalister Mathews CBE FRSE FZS FLS (10 September 1876 – 27 March 1949) was an Australian-born amateur ornithologist who spent most of his later life in England.

Life

He was born in Biamble in New South Wales the son of Robert H. Ma ...

CBE, FRSE (1876–1949), their third child, won international renown as an ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

. He donated his outstanding collection of Australian books to the National Library of Australia. His collection of bird skins, sold to Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was presen ...

in the 1920s, is in the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

, New York City.

After two years in Singleton Mathews resigned from his post as a licensed surveyor. From that time his surveying was confined to a part-time practice. From May 1882 until March 1883 Robert and Mary made a world tour, visiting the United States, Britain and possibly Europe. In Ireland, Mathews visited his parents' village of Claudy, seemingly unaware that his father had been suspected of involvement in the murder of James Lampen.

Legal career

Mathews was appointed a justice of the peace for the colonies of Queensland and South Australia in 1875 and for New South Wales in 1883. This allowed him to serve as a magistrate in local courts. He did this regularly after he moved to Singleton where he also served as district coroner. This experience inspired his first publication, ''Handbook to Magisterial Inquiries in New South Wales: Being a Practical Guide for Justices of the Peace in Holding Inquiries in Lieu of Inquests'' (1888). When Mathews became interested in anthropology, he found his status as a magistrate advantageous. Contacts in the police force supplied information on Aboriginal ceremonies while others informed him about the location of potential informants or collected data on his behalf. Mathews' coronial work exposed him to the sufferings of Aboriginal people in the districts around Singleton. He officiated at the magisterial inquiry into the death of a Singleton Aborigine known as Dick who died of malnutrition and exposure in 1886. James S. White, the minister of the Singleton Presbyterian Church where Mathews worshipped, was an active campaigner for Aboriginal rights. Mathews was friendly with White, but never became a political agitator, preferring instead to document the complexity of Aboriginal culture. In 1889 the Mathews family moved from Singleton toParramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

in western Sydney where his sons attended The King's School, Parramatta

The King's School is an Education in Australia#Non-government schools, independent Anglican Church of Australia, Anglican, Pre-school education, early learning, primary school, primary and secondary school, secondary day and boarding school, boardi ...

.

Contribution to anthropology

In early 1892 Mathews returned to the Hunter Valley to survey a pastoral property near the hamlet ofMilbrodale, New South Wales

Milbrodale is a village in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia. It is in the local government area of Singleton Council.

Description

Milbrodale is set in a rural area 23 kilometres south of Singleton. To the north of Milbrodale is D ...

. A worker on the property pointed out a rock shelter where a large man-like figure had been painted by Aboriginal artists. Mathews measured and drew the painting and documented hand stencils

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 y ...

in other caves in the vicinity. From these observations he prepared a paper that he read before the Royal Society of New South Wales and subsequently published in the 1893 volume of the Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. He identified the human figure as a depiction of the ancestral being, Baiame

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Baiame (or Biame, Baayami, Baayama or Byamee) was the creator god and sky father in the Dreaming of several Aboriginal Australian peoples of south-eastern Australia, such as the Wonnarua, Kamilaroi, Guring ...

(also spelled Baiamai and Baiami). The encounter with the Baiame site, and the favourable reception of Mathews' paper by the Royal Society of New South Wales, marked a turning point in his career. His biographer, the Australian historian Martin Thomas, describes it as the onset of his "ethnomania". Mathews was further encouraged when he prepared a long paper on Sydney rock art which was awarded the Royal Society's Bronze Medal essay prize for 1894.

From this time, Mathews became a fanatical student of Aboriginal society. He familiarised himself with the fledgling discipline of anthropology by studying in the library of the Royal Society of New South Wales which exchanged publications with 400 other scholarly and scientific institutes around the world. He also studied at the Public Library in Sydney (now the State Library of New South Wales

The State Library of New South Wales, part of which is known as the Mitchell Library, is a large heritage-listed special collections, reference and research library open to the public and is one of the oldest libraries in Australia. Establish ...

). Mathews' work would now be classified as social or cultural anthropology. He did not practise physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct Hominini, hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly ...

or collect human remains.

In addition to documentation of rock art, which appears in 23 published papers, Mathews published on the following themes: kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

and marriage rules; male initiation

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformation ...

; mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

; and linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

. He capitalised on the considerable international interest in Aboriginal Australians in the Victorian and Edwardian periods. His reports were read and cited by major social scientists including Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim ( or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, al ...

and van Gennep. Apart from a few short books and booklets, Mathews published almost entirely in learned journals, including ''Journal of the Anthropological Institute'', American Anthropologist

''American Anthropologist'' is the flagship journal of the American Anthropological Association (AAA), published quarterly by Wiley. The "New Series" began in 1899 under an editorial board that included Franz Boas, Daniel G. Brinton, and John W ...

, ''American Antiquarian'', ''Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris'', and ''Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft''. In addition to these specialist anthropological journals, he published in general scientific periodicals including Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' is a quarterly journal published by the American Philosophical Society since 1838. The journal contains papers which have been read at meetings of the American Philosophical Society each April ...

and the journals of various Australian royal societies including the Royal Australasian Geographical Society (Queensland Branch).

Mathews gathered information by forging links with Aboriginal communities that he visited in person. This was his preferred method of data collection, and he criticised Howitt and Lorimer Fison

Lorimer Fison (9 November 1832 – 29 December 1907) was an Australian anthropologist, Methodist minister and journalist.

Early life

Fison was born at Barningham, Suffolk, England, the son of Thomas Fison, a prosperous landowner, and his wife ...

for "not having gone out among the blacks themselves in all cases." However, Mathews' personal investigations were confined to southeast Australia while his publications concerned all Australian colonies (states from 1901) except Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. When writing about areas he could not personally visit, he used data supplied by rural settlers whom he persuaded to collect information according to his instructions. The R. H. Mathews Papers contain many examples of this incoming correspondence.

Kinship and marriage rules

Of Mathews' 171 publications, 71 are to do with Aboriginal kinship, totems or the rules of marriage. His first publication on kinship was read before the Queensland branch of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia in 1894. It concerns theKamilaroi

The Gamilaraay, also known as Gomeroi, Kamilaroi, Kamillaroi and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people whose lands extend from New South Wales to southern Queensland. They form one of the four largest Indigenous nations in Aust ...

people of New South Wales whose country he knew from his surveying. Mathews noted that the Kamiliaroi community was divided into two cardinal groups, these days known as moieties (although Mathews more often called them "phratries" or less often "cycles"). Each moiety was divided into a further two sections. Particular sections (from opposite moieties) were expected to intermarry. The community was also divided into totems, which were also taken into consideration when marriages were being arranged. Particular totemic groups were expected to intermarry.

Mathews noted that marriage rules similar to those of the Kamilaroi occurred across much of Australia. Some communities had intermarrying moieties without further divisions within the moiety groups. Others had moieties divided into four sections (now known as sub-sections). He plotted the distribution of marriage rules and other cultural traits in his "Map Showing Boundaries of the Several Nations of Australia", published by the American Philosophical Society in 1900.

Throughout his studies of Aboriginal kinship, Mathews claimed that some marriages occurred that were outside the standard marriage rules as generally understood by the community, although they were nonetheless accepted. He called them "irregular" marriages and argued that a further set of rules governed these relationships. Despite these departures from the standard rules, it remained a highly ordered social system. Mathews pointed out that in Kamilaroi society there were some marriages, such as those between people of the same totem, that were never deemed acceptable. Mathews' rival Howitt denounced these findings, arguing that this information was imparted by "degraded" tribes, corrupted by European influence. However, later anthropologists, including Adolphus Peter Elkin

Adolphus Peter Elkin (27 March 1891 – 9 July 1979) was an Anglican clergyman, an influential Australian anthropologist during the mid twentieth century and a proponent of the assimilation of Indigenous Australians.

Early life

Elkin was born a ...

, endorsed Mathews' interpretation.

Mathews' approach to kinship was very different from that of Howitt who, as John Mulvaney has written, sought "to lay bare the essentials of primeval society, on the assumption that Australia was a storehouse of fossil customs." Mathews reacted against this approach, which was based on the social evolutionary ideas of Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social evol ...

, a patron of both Howitt and his collaborator Fison. Howitt and Fison argued that the vestiges of a primitive form of social organisation, called "group marriage

Group marriage or conjoint marriage is a marital arrangement where three or more adults enter into sexual, affective, romantic, or otherwise intimate short- or long-term partnerships, and share in any combination of finances, residences, care ...

", were evident in Aboriginal marriage rules. Group marriage, as defined by Morgan, presupposed that groups of men who called each other "brother" had collective conjugal rights over groups of women who called each other "sister". Thomas argues that Mathews found the idea of group marriage in Aboriginal society "counterintuitive" because "the requirements of totems and sections made marriage a highly restrictive business." The idea that group marriage exists in Aboriginal Australia is now dismissed by anthropological authorities as "one of the most notable fantasies in the history of anthropology."

Male initiation

Mathews believed that ceremonial life was integral to the social cohesion of Aboriginal communities. Initiation, he explained, was "a great educational institution" intended to strengthen the civil authority of the elders of the tribe. Mathews' first publication on initiation was a description of a Bora ceremony, held by Kamilaroi people at Gundabloui in 1894. He returned to the subject of Kamilaroi initiation in his last paper, "Description of Two Bora Grounds of the Kamilaroi Tribe" (1917), published the year before his death. In the intervening years, Mathews wrote extensively on ceremonial life, mostly in southeast Australia. More limited descriptions of ceremonies in South Australia and the Northern Territory were developed from data supplied by correspondents. Of his 171 anthropological publications, 50 are partly or wholly concerned with ceremony. The majority consist of a detailed description of the initiation ritual practised by a particular community. By 1897, Mathews could claim to have documented the male initiation ceremonies of about three quarters of the land mass of New South Wales. Mathews wrote primarily about the early stages of male initiation. However, he published some data on female initiation in Victoria and he was attentive to the activities that occurred in the women's camps while neophytes were out in the bush being inducted into rituals by the men. Mathews documented initiation at a time when the ceremonies were endangered by colonisation and the consequent loss of access to sacred ceremonial sites. Many of the performers in ceremony who were known to Mathews were employed in the pastoral industry. Mathews' reports show that these historical changes found expression in ceremonial life. Motifs of cattle, locomotives, horses and white people were carved into the ground at ceremonial sites in New South Wales. Mathews' work on Kamilaroi initiation was cited extensively in a famous debate between Lang and Hartland about whether Aborigines "possessed the conception of a moral Being". Much of Mathews' research on ceremony was conducted during preparatory and rehearsal periods, rather than during the initiation rituals themselves. Thomas suggests that this may have been intentional on the part of Mathews' informants, since it allowed them to control what secret-sacred information was revealed to an outsider. That Mathews was permitted even this degree of access is evidence of the degree to which he was trusted. He was given a number of sacred instruments relating to initiation ceremonies, now in the collection of the Australian Museum. Information documented by Janet Mathews, originating from Aboriginal elders on the South Coast of New South Wales in the 1960s, indicates that Mathews was himself initiated. Thomas argues that Mathews' refusal to write directly about these experiences shows that his loyalty to the secret culture was "more important than whatever kudos he might have won as an anthropologist in revealing these secrets to the world."Mythology

Mathews' first contribution to the study of myth was a series of seven legends from various parts of New South Wales, published in 1898 as "Folklore of the Australian Aborigines" by the anthropological magazine ''Science of Man''. He republished them as a short book the following year. Over the next decade, Mathews published another dozen articles describing Aboriginal myths. While a few legends from Western Australia were documented by a correspondent, the great bulk of Mathews' folklore research was done in person. Mathews' interest in mythology connected with the British interest infolklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

study that was a serious branch of inquiry during his lifetime. The Folklore Society

The Folklore Society (FLS) is a national association in the United Kingdom for the study of folklore.

It was founded in London in 1878 to study traditional vernacular culture, including traditional music, song, dance and drama, narrative, arts an ...

, formed in 1878, was dedicated to the study of traditional music, customs, folk art, fairy tales and other vernacular traditions. The society published ''Folk-Lore'', an internationally distributed journal, to which Mathews contributed five articles.

In keeping with the ''Folk-Lore'' style, Mathews tended to rephrase Aboriginal narratives into respectable English. This was acceptable to his allies Hartland and Lang, both prominent in folklore studies. However, Mathews' rephrasing was queried by Moritz von Leonhardi

Moritz Freiherr von Leonhardi (9 March 1856 – 27 October 1910) was a German anthropologist.

Life and work

Leonhardi was the son of the Minister Plenipotentiary Ludwig (Louis) Freiherr von Leonhardi and Luise, née Bennigsen. He grew up in ...

, the German editor and publisher, with whom he corresponded.

Despite these limitations, Mathews' publications and unpublished notes preserve significant examples of Aboriginal folklore that might otherwise have been lost. Mathews' most substantial documentation of Aboriginal mythology can be found in his account of the creation of the Blue Mountains, as told by Gundangara (or Gundungurra) people. The story involves an epic chase between the quoll Mirragan and the great fish Gurangatch who tore up the ground to create rivers and valleys. Mathews' surveying background and his interest in topography made him attentive to the route of the journey.

Linguistics

The first language documented by R. H. Mathews was Gundungurra in a paper co-authored with Mary Everitt, a Sydney school teacher, dated 1900. From that time, linguistic study was a major part of his research. Language elicitation can be found in 36 of his 171 works of anthropology. His linguistic writings describe a total of 53 Australian languages or dialects. Most of Mathews' linguistic research was conducted in person during visits to Aboriginal camps or settlements. He wrote in his study of Kurnu (a major dialect of the Paakantji language, spoken in western New South Wales): "I personally collected the following elements of the language in Kurnu territory, from reliable and intelligent elders of both sexes." A few of his linguistic studies were carried out with aid of correspondents. A 210 word vocabulary of the Jingili language was prepared with the aid of a Northern Territory grazier. The Lutheran missionary and anthropologistCarl Strehlow

Carl Friedrich Theodor Strehlow (23 December 1871 – 20 October 1922) was an anthropologist, linguist and genealogist who served on two Lutheran missions in remote parts of Australia from May 1892 to October 1922. He was at Killalpaninna Missio ...

supplied information for a paper on Luritja, spoken in Central Australia. Mathews' publications seldom name the Aboriginal people who tutored him in language, but this information can often be found in notebooks or offprints of articles among the R. H. Mathews Papers.

A consistent template was used throughout Mathews' linguistic writings. First, the grammar was explained. This was followed by vocabulary, first with the word in English and then its equivalent in the Aboriginal language. Words are grouped in categories which were loosely replicated in each article: "The Family", "The Human Body", "Natural Surroundings", "Mammals", "Birds", "Fishes", "Reptiles", "Invertebrates", "Adjectives" and "Verbs". Mathews' vocabularies typically number about 300 words, rising on occasion to 460. Mathews studied language in this manner because he believed that comparative linguistic study would provide evidence of the successive waves of migration into Australia when the continent was originally populated.

Mathews used a system of orthography developed from advice on the elicitation of native terms, circulated by the Royal Geographical Society. Mathews' documentation was not sufficiently extensive so as to allow someone to learn or speak the language. Even so, his work constitutes an important historical record of many tongues that are no longer spoken. It has been used extensively in more recent historical investigations of Aboriginal linguistics.

Conflict with rivals

In a letter toAlfred William Howitt

Alfred William Howitt , (17 April 1830 – 7 March 1908), also known by author abbreviation A.W. Howitt, was an Australian anthropologist, explorer and naturalist. He was known for leading the Victorian Relief Expedition, which set out to es ...

, Walter Baldwin Spencer

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (23 June 1860 – 14 July 1929), commonly referred to as Baldwin Spencer, was a British-Australian evolutionary biologist, anthropologist and ethnologist.

He is known for his fieldwork with Aboriginal peoples in ...

said of Mathews that "I don't know whether to admire most his impudence his boldness or his mendacity—they are all of a very high order and seldom combined to so high a degree in one mortal man." Spencer said of Mathews' writings that they merely "corroborate or make use of" other scholarship "without adding any matter of importance".

Spencer provided little explanation of why he objected to Mathews so strongly. Theoretical differences are thought to have been a factor. Spencer believed in social evolution

{{unreferenced, date=February 2015

''Social Evolution'' is the title of an essay by Benjamin Kidd, which became available as a book published by Macmillan and co London in 1894. In it, Kidd discusses the basis for society as an evolving phenomenon ...

and group marriage

Group marriage or conjoint marriage is a marital arrangement where three or more adults enter into sexual, affective, romantic, or otherwise intimate short- or long-term partnerships, and share in any combination of finances, residences, care ...

, whereas Mathews was sympathetic to ideas of cultural diffusion

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technologi ...

. Mathews corresponded with W. H. R. Rivers

William Halse Rivers Rivers FRS FRAI ( – ) was an English anthropologist, neurologist, ethnologist and psychiatrist known for treatment of First World War officers suffering shell shock, so they could be returned to combat. Rivers' most f ...

, who became a major proponent of diffusionist theories. Early in their anthropological careers, Mathews and the Melbourne-based Spencer themselves corresponded, and they were sufficiently close in 1896 for Spencer to be listed as having communicated Mathews' article "The Bora of the Kamilaroi Tribes" to the Royal Society of Victoria. By 1898 they had completely fallen out and Spencer commenced a behind-the-scenes campaign against Mathews. Spencer wrote to British anthropologists, among them Sir James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janu ...

, urging them never to quote him. Frazer agreed, promising Spencer that "I shall not even mention him athewsor any of his multitudinous writings."

Spencer was closely allied to A. W. Howitt who was also hostile to Mathews. Mathews had initially assumed a collegial attitude to Howitt, describing him in 1896 as a "friend and co-worker". Until 1898, Mathews' references to Howitt's work were invariably respectful, even when their opinions differed. Howitt, however, consistently refused to acknowledge Mathews' scholarship, possibly because Mathews had queried his reports that the kinship systems of south Queensland descended through the paternal line. Mathews was enraged when Howitt's magnum opus ''The Native Tribes of South-East Australia'' was published in 1904. By that time Mathews had published more than 100 works of anthropology, but he received not a footnote in Howitt's book. The extent to which Mathews was being overlooked by his Australian contemporaries became apparent to British anthropologists. Northcote W. Thomas

Northcote Whitridge Thomas (1868–1936) was a British anthropologist and psychical researcher.

Career

Thomas was born in Oswestry, Shropshire. He studied history and graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge with a BA in 1890 and an MA in 1894. ...

observed in 1906 that Mathews had written "numerous articles", all of which had "either been ignored or dismissed in a footnote by experts such as Dr. Howitt and Prof. Baldwin Spencer".

In 1907 Mathews published a critique of Howitt and Spencer in ''Nature'' in which he complained that Howitt had consistently overlooked his own work. Considering it too prominent a forum to ignore, Howitt wrote a rejoinder and thus engaged in dialogue with Mathews for the first time. Howitt made the unlikely claim that he had only ever seen two publications by Mathews "neither of which recommended itself to me by its accuracy". Mathews replied, questioning the veracity of this assertion.

Mathews and Howitt subsequently debated each other at greater length in ''American Antiquarian''. Howitt was by this time mortally ill. His final contribution to anthropology, written on his death bed, was a denunciation of Mathews titled "A Message to Anthropologists". It was posthumously printed as a circular letter by members of the Howitt family and posted to a list of anthropological luminaries that included Henri Hubert

Henri Hubert (23 June 1872 – 25 May 1927) was a French archaeologist and sociologist of comparative religion who is best known for his work on the Celts and his collaboration with Marcel Mauss and other members of the Année Sociologique.

L ...

, Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim ( or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, al ...

, Marcel Mauss

Marcel Mauss (; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and a ...

, Arnold van Gennep

Arnold van Gennep, in full Charles-Arnold Kurr van Gennep (23 April 1873 – 7 May 1957) was a Dutch–German- French ethnographer and folklorist.

Biography

He was born in Ludwigsburg, in the Kingdom of Württemberg (since 1871, part of the Ger ...

, Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

, Prince Roland Bonaparte

Roland Napoléon Bonaparte, 6th Prince of Canino and Musignano (19 May 1858 – 14 April 1924) was a French prince and president of the Société de Géographie from 1910 until his death. He was the last male-lineage descendant of Lucien Bonaparte ...

and Carl Lumholtz

Carl Sofus Lumholtz (23 April 1851 – 5 May 1922) was a Norwegian explorer and ethnographer, best known for his meticulous field research and ethnographic publications on indigenous cultures of Australia and Mexico.

Biography

Born in Fåberg, N ...

. It was also published in ''Revue des Études Ethnographiques et Sociologiques''. Martin Thomas argues that "A Message to Anthropologists" did significant damage to Mathews' reputation.

Impact

Thomas notes that professional anthropologists have often been cautious in acknowledging the contribution of their "amateur" forebears. Mathews had few champions among academic anthropologists until A. P. Elkin became interested in his work. In an obituary ofAlfred Radcliffe-Brown

Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, FBA (born Alfred Reginald Brown; 17 January 1881 – 24 October 1955) was an English social anthropologist who helped further develop the theory of structural functionalism.

Biography

Alfred Reginald Radcli ...

dated 1956, Elkin declared that Mathews' work on Australian kinship marked a significant intellectual breakthrough. He listed eleven key achievements in the field of kinship study, including Mathews' realisation that the totemic heroes "were related to one another in the same kinship manner as human beings were related: in other words, that they were part of the same social order." More controversially, Elkin argued that anyone "familiar with Radcliffe-Brown's writings on this subject since 1913 will realise the extent to which he used Mathews's concepts and generalisations." Elkin claimed Radcliffe-Brown was familiar with Mathews's writings but, regarding him as an amateur, "underestimated his ability for careful recording and sound generalisation. This, however, did not prevent him adopting the results of much which Mathews had accomplished." Twenty years later, Elkin built substantially on his earlier argument for Mathews' importance. This was published as a three-part journal article titled "R. H. Mathews: His Contribution to Aboriginal Studies". A draft "Part IV" in the University of Sydney Archives indicates that Elkin was planning further writings on Mathews before his death in 1979.

Another early champion was Norman Tindale

Norman Barnett Tindale AO (12 October 1900 – 19 November 1993) was an Australian anthropologist, archaeologist, entomologist and ethnologist.

Life

Tindale was born in Perth, Western Australia in 1900. His family moved to Tokyo and lived ther ...

who found Mathews' understanding of topography and cartography invaluable to his project of mapping tribal boundaries. The bibliography of Tindale's ''Aboriginal Tribes of Australia'' reveals the extensive use he made Mathews' writings. Tindale wrote in 1958 that in "going through Mathews' papers for the purpose of checking the second edition of my tribal map and its data, I have been more than ever impressed with the vast scope and general accuracy of this work. Despite earlier critics I am coming to believe that he was our greatest recorder of primary anthropological data."

Disagreement about the value of Mathews' work has continued. In a 1984 article the historian Diane E. Barwick, made a damning appraisal of Mathews, criticising his Victorian research for perpetrating a "sometimes ignorant and sometimes deliberate distortion hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

has so muddled the ethnographic record …". Barwick claimed that from 1898 Mathews "contradicted, ridiculed or ignored" the "careful ethnographic reports" of Howitt for whom he had an "almost pathological jealousy

Pathological jealousy, also known as morbid jealousy, Othello syndrome or delusional jealousy, is a psychological disorder in which a person is preoccupied with the thought that their spouse or sexual partner is being unfaithful without having a ...

". The contemporary anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose and colleagues take the opposite view, describing Mathews as "a more sober and thorough researcher" than Howitt. They claim that "Mathews did not share Howitt's penchant for suppressing the particular in favour of the grand theory, or for suppressing women in favour of men." Unusually for a male anthropologist, he acknowledged "the existence of women's law and ritual."

The enactment of Native Title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty under settler colonialism. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, ...

legislation in Australia has created new interest in Mathews' work. His writings are now routinely cited in Native Title claims put forward by Aboriginal claimants.

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* *Robert Hamilton Mathews papers

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mathews, Robert Hamilton 1841 births 1918 deaths Australian anthropologists Linguists from Australia